In mixed crop livestock systems found in the Nkayi district of western Zimbabwe, crop production is rainfed, dominated by maize, with small grains and legumes as alternative crops. Cattle play an important role in the provision of draft power and manure, convert biomass into utilities, income and risk spreading.

Average annual rainfall ranges from 450–650 mm, making the system vulnerable to erratic rainfall with a drought frequency of one in every five years. The soils vary from infertile deep Kalahari sands, to clay and clay loams that are also nutrient-deficient due to continuous cropping without soil replenishment.

Farmers use mainly a mono-cereal cropping system and add low amounts of inorganic and organic soil amendments. Natural pasture provides the main feed for livestock, and biomass availability is seasonal. During the dry season there is insufficient biomass of poor quality.

With low farm productivity, not much support for adaptation strategies, and limited investment in markets, levels of income poverty and food insecurity are high. 77% live below international poverty line, one in five is extremely poor. This is although for national agricultural development and adaptation strategies improving food security is high on the agenda.

Nkayi (Zimbabwe) regional study

Adaptation and mitigation benefits for mixed crop livestock farming systems

In Nkayi District in Zimbabwe, mixed crop livestock farmers predominantly grow maize, with smaller portions of small grains and a variety of legumes; many also keep cattle and goats. Irregular rains, poor soil fertility and dry season feed shortages pose major challenges, made worse by the impacts of changing climate. How can farmers improve their livelihoods and food security, adapt and mitigate the impacts of climate change?

More information can be found in the policy brief 'Climate change and adaptation impacts in mixed crop-livestock systems in south west Zimbabwe'.

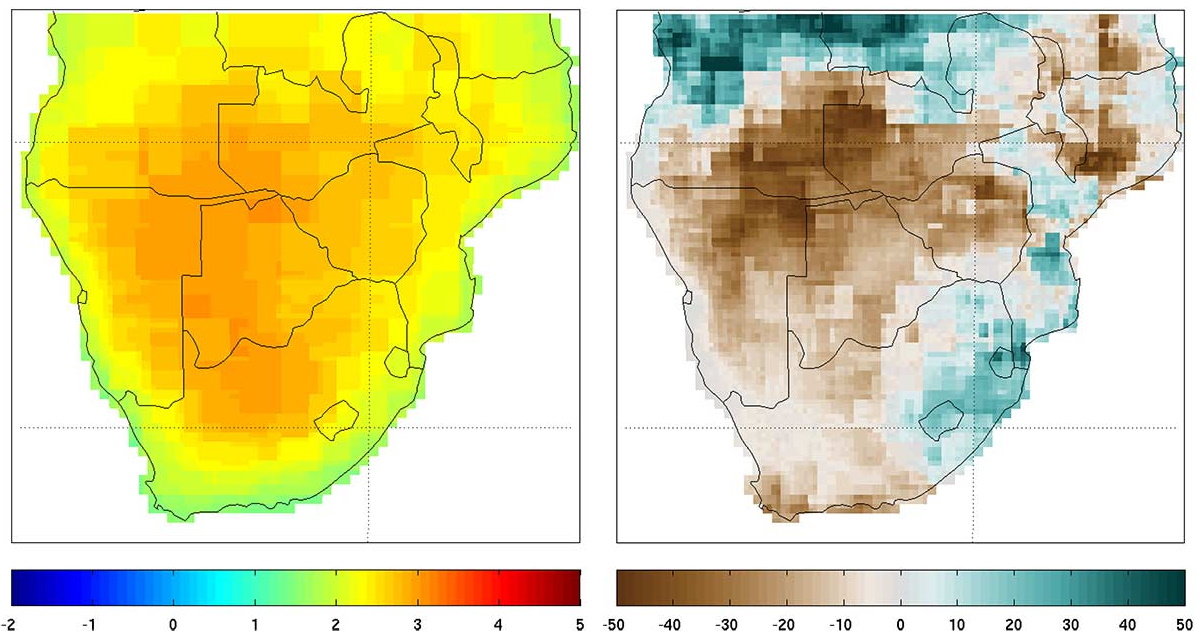

By mid-century, temperature is expected to rise whereas rainfall will decrease and become more variable. This will worsen poverty and food insecurity for highly vulnerable rural communities.

Long-term average maximum and minimum temperatures are 26.9◦C and 13.4◦C, respectively. Temperatures are projected to increase, by up to 3C, affecting plant development, shortening the time for biomass accumulation, reduce crop yields and change rangeland plant diversity. Higher temperatures also affect livestock, interplay of feed gaps, heat stress and diseases.

Rainfall projections are less certain; rainy seasons are likely to start later and there are indications that rainfall will decrease, by up to 25%.

Current system

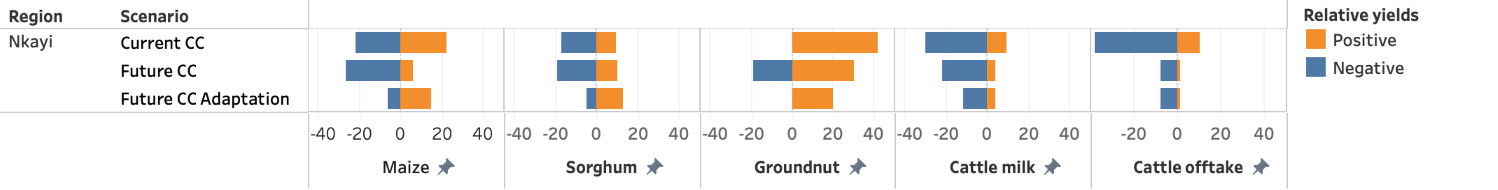

If climate effects will affect farms with currently applied crop and livestock management practices and low levels of productivity, the projected losses will be modest, and affect crops and livestock differently.

Maize yields will be reduced, mainly due to increased temperature, but higher quality soils will have higher yields.

Groundnuts will benefit, as higher CO2 levels off-set the impacts of higher temperature. Yields will generally be higher under more humid conditions, due to less water stress.

Climate change reduces grass growth and crop residue yields, aggravating feed gaps that affect livestock production. Farmers with large cattle herds are particularly affected by reduced cattle productivity.

Climate change will increase poverty among for those with large cattle herds; those with few cattle are already impoverished.

Future system

Future changes in the farming systems, with investments in markets and services and improved access to technologies, will lead to more diversified and better integrated crop livestock systems. Higher yields on soils with improved fertility will compensate for the losses of climate change. Improving soil fertility will hence be even more important in the future for capitalizing on improved crop varieties and climate factors such as rainfall and CO2 for legumes in particular.

With greater efforts on supplementary feeding in future, livestock will be less affected by climate change. Farmers with large herds will still be sensitive, so that the benefits from economic development are not lost due to climate change

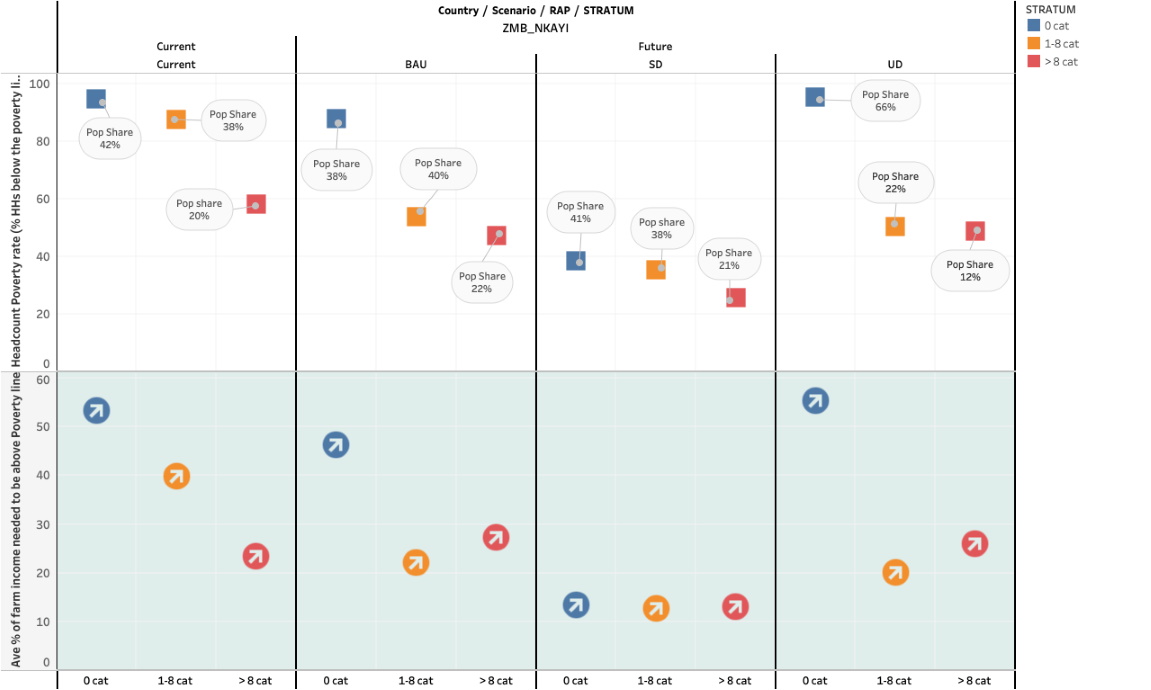

Vulnerability and poverty

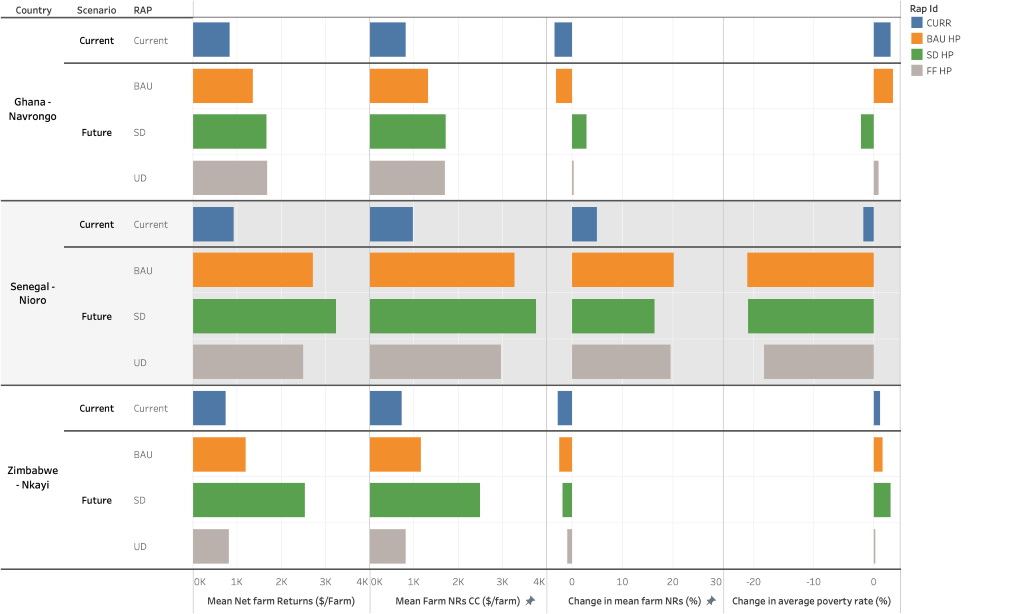

Farms are better off in future when socio-economic conditions are improved: they off-set the negative impacts of climate change. Still, climate change will be felt by those with large cattle herds, due to the impacts of feed gaps on livestock productivity and off-take.

Poverty will not change much for those who are already poor. They will produce more groundnuts that are less sensitive to climate change, or depend more on off-farm income.

Although farms will be less vulnerable in future as compared to today, the levels of vulnerability are still high. It is important to include social protection mechanisms and design adaptation strategies that improve farms resilience to climate change.

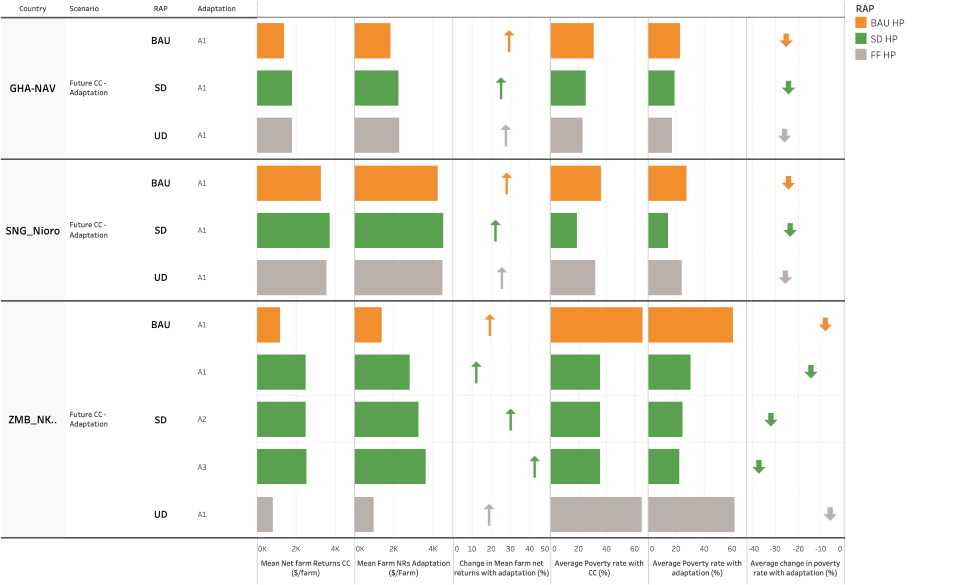

Future climate, socio-economic conditions and emission scenarios or "Representative Agricultural Pathways" were developed to explore the performance of agricultural systems under the range of conditions considered relevant, by stakeholders and scientists.

Two plausible future states were compared: one representing sustainable development (Green Road), the other unsustainable fossil fuel intense development (Grey Road).

For the two scenarios, different adaptation packages were tested to improve farm productivity. Under the Sustainable Development scenario, the agricultural sector supports a climate resilient and low carbon economy (adaptation package 1), whereas under unsustainable development there is low commitment to funding climate change adaptation and mitigation (adaptation package 2).

The research relies on inputs from experts and stakeholders who understand local farming systems, and thus provides a process to effectively bring diverse knowledge in the development and evaluation of context specific scenarios and adaptation options. These methods can be used to support the targeting of agricultural interventions to farm types, for design and impact assessment of context specific safety-net, food security or market oriented intervention packages.

A series of expert meetings were held with researchers and government extension representatives involved in agricultural development in Nkayi district, to develop and validate outcomes from scenarios and adaptation packages. In a next step, the local level representatives were engaged with national level experts to verify the consistency between national policies and local level implementation.

AgMIP key messages included:

There is potential for these methods to test the usefulness of context specific modifications to raise farm incomes, reduce vulnerability to climate change and enhance resilience.

The dialogue around the outcomes helps to distill what changes in the institutional or policy environment would be needed to facilitate uptake and impacts.

Incorporating greenhouse gas emissions as part of a technology assessment allows to estimate trade-offs with equitable development outcomes.

Further work on the social inclusiveness within crop livestock systems systems in the context of climate smart agriculture is clearly warranted

The results have not been put into practice yet, but we can review the results of the research process. They give policy makers a frame, vision for future, in its complexity and allow policy makers to see possibilities that exist and plan for those futures. They also point out the need for more nuanced input and support strategies, where national programs are rolled out without thorough consideration of variation in the country. Dryland cereals and grain legumes for instance are underrepresented in input support programs, despite their contributions as climate resilient and smart foods.

Some dimensions were missing or not sufficiently addressed, such as small livestock, and health and diseases, as they interact with climate change impacts. Greater attention should be spent on including soil fertility, irrigation, water availability and water use efficiency.

The low levels of productivity and farm income impact negatively on the ability to adapt to climate change. They show the basis for social protection programs, how to plan for it, given dimensions in climatic parameters.

The approach is useful to inform communities of practice engaging in climate change adaptation planning at the local level and to bring to the attention the need for adaptation that is adequately sensitive to local circumstances and context.

References to scientific papers, websites and other relevant resources

References

- Descheemaeker K, Zijlstra M, Masikati P, Crespo O, Homann-Kee Tui S (2018) Effects of climate change and adaptation on the livestock component of mixed farming systems: A modelling study from semi-arid Zimbabwe. Agric Syst 159: 282-295.

- Homann-Kee Tui S., Descheemaeker K., Masikati P., Sisito, G., Valdivia, R., Crespo, O., Claessens L. (2021) Climate Change Impacts and Adaptation for Dryland Farming Systems in Zimbabwe: A Stakeholder-Driven Integrated Multi-Model Assessment. Climatic Change. Accepted for publication.

- Homann-Kee Tui, S., Masikati, P., Descheemaeker, K., Sisito, G., Francis, B., Senda, T., Crespo, O., Moyo, E.N., Valdivia, R. (2021) Transforming Smallholder Crop–Livestock Systems in the Face of Climate Change: Stakeholder-Driven Multi-Model Research in Semi-Arid Zimbabwe. In: Handbook of Climate Change and Agroecosystems: Climate Change and Farming System Planning in Africa and South Asia: AgMIP Stakeholder-driven Research (In 2 Parts). Vol. 5, 217-276. World Scientific Publishing Company. World Scientific Publishing. [Rosenzweig, C., C.Z. Mutter and E. Mencos Contreras (eds.)].

- Masikati P, Manschadi A, van Rooyen A, Hargreaves J (2013) Maize–mucuna rotation: a technology to improve water productivity in smallholder farming systems. Agric Syst 123: 62–70.

-

Masikati P, Descheemaeker K, Crespo O (2019) Understanding the role of soils and management on crops in the face of climate uncertainty in Zimbabwe: A sensitivity analysis. Chapter 5. In: TS Rosenstock, A Nowak, E Girvetz eds. The Climate-Smart Agriculture Papers. Investigating the Business of a Productive, Resilient and Low Emission Future. Springer Open. 49-64.